WASTED DATA

When garbage overflows data

Waste Management in Nigeria and Lagos: the data problem

One of the main structural challenges to effectively addressing waste management in Nigeria, and especially in Lagos, is the notable lack of reliable and consistent data. This is not merely a technical problem: it directly affects public policy formulation, resource allocation, investment attraction, and international cooperation. Designing sustainable solutions becomes extremely complex when the available figures are contradictory, incomplete, or simply non-existent.

Although there is no precise national data, it is estimated that Nigeria generates more than 0.65 kilograms of waste per person per day. This figure, based on consumption patterns in countries with similar middle- and low-income profiles, would imply an annual generation exceeding 40 million tonnes—more than half of all the waste produced in Sub-Saharan Africa, according to ICEX estimates. If current trends continue, this figure could surpass 107 million tonnes by 2050.

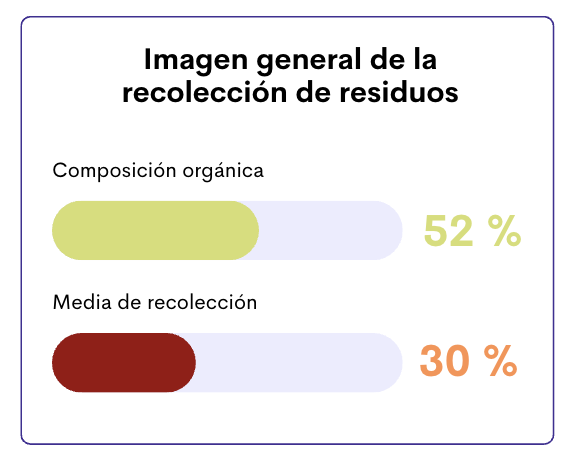

The current municipal solid waste management system in Nigeria is rudimentary and inefficient. Facilities are scarce and outdated, collection coverage is low, and treatment processes are limited. On average, only about 30% of waste is formally collected, with significantly lower coverage in low-income areas. In some regions, this coverage doesn’t even reach 10%. As a result, a large portion of the population turns to informal waste disposal methods such as open dumping, burning, or discarding waste into canals—further worsening public health and environmental degradation.

Estimates regarding the final destination of collected waste also vary greatly. Some studies (Richie and Max, 2022) suggest that more than 80% of waste ends up in uncontrolled dumpsites, while the World Bank’s “What a Waste 2.0” report raises this figure to 93% for low-income countries.

Only a very small fraction is deposited in sanitary landfills or subjected to any form of treatment.

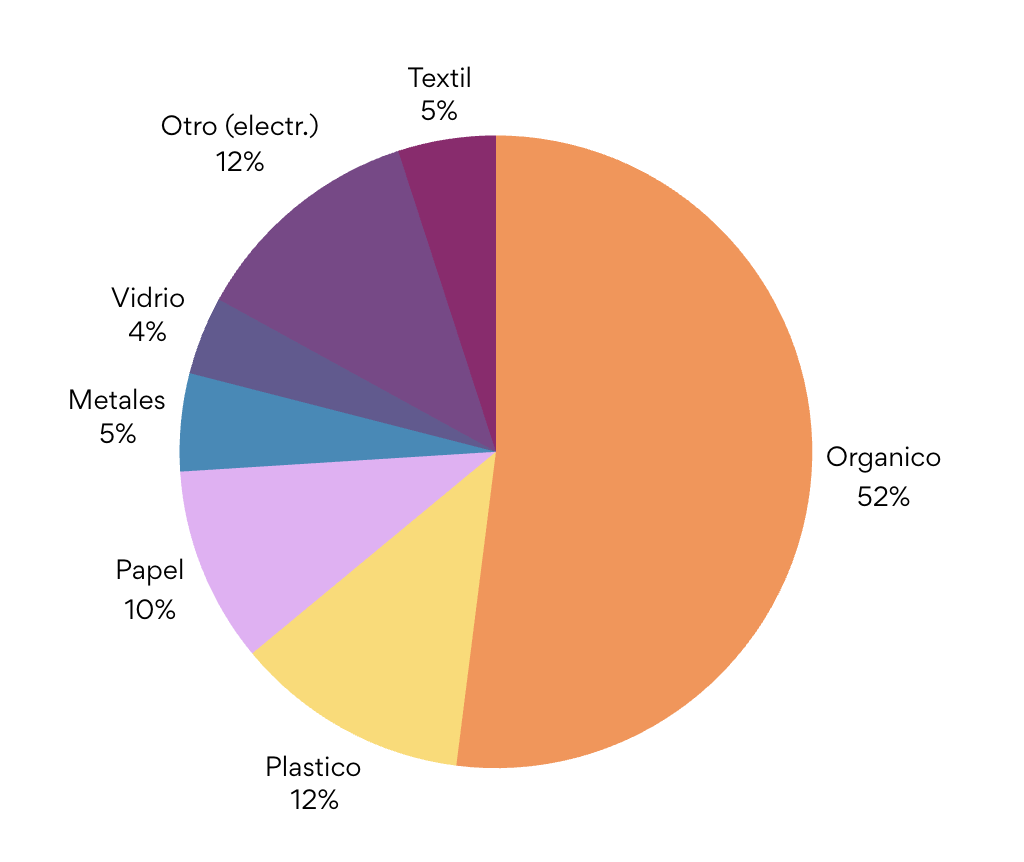

As for waste composition, available data shows a predominance of organic waste (around 52%), followed by plastics (12%), paper and cardboard (10%), metals (5%), glass (4%), textiles (5%), and other types of waste (12%), including electronic and sanitary waste (MDPI, 2024). This profile is typical of emerging economies, where recyclable materials account for a smaller share of total waste.

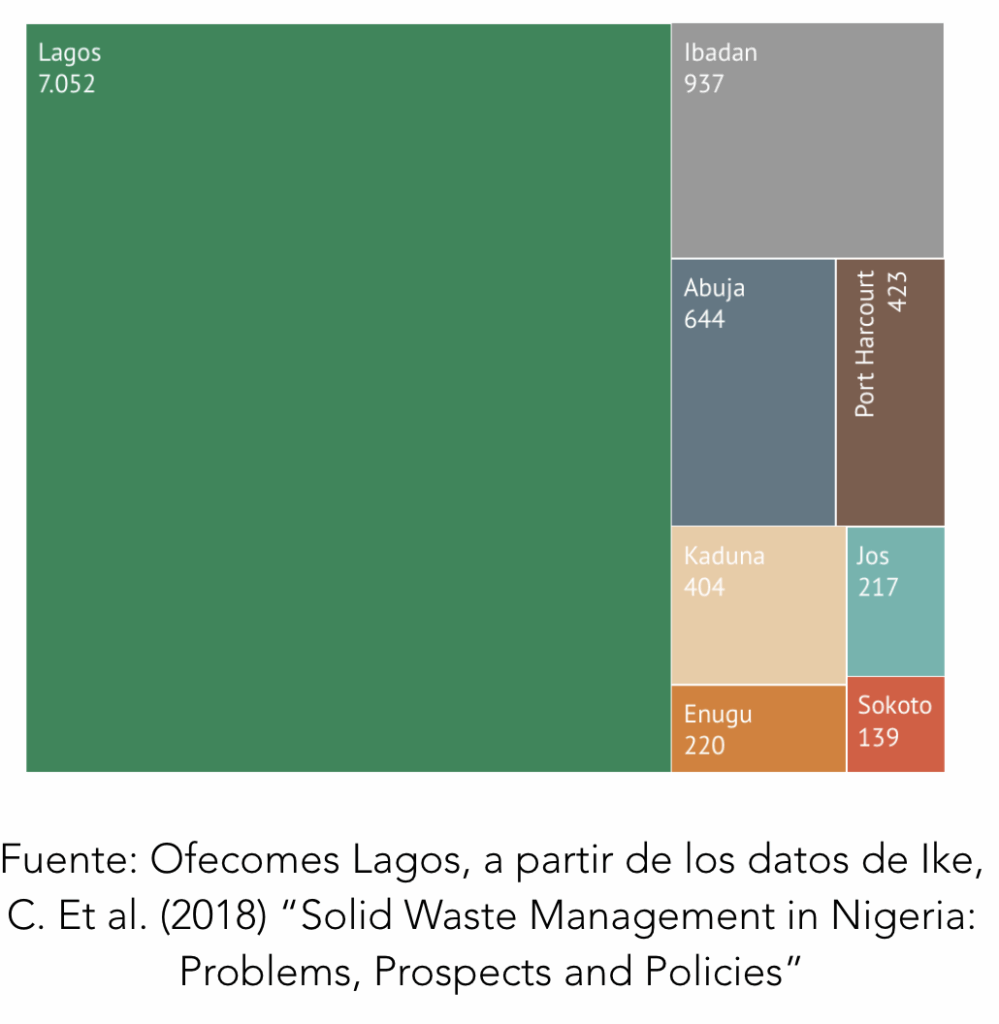

In this context, Lagos stands out as a paradigmatic case. Despite being Nigeria’s largest and most urbanised city, the situation does not significantly improve compared to the national picture. In fact, data discrepancies are just as acute. While the World Bank estimates that Lagos generates between 13,000 and 15,000 tonnes of waste daily (MSW), earlier reports such as those from OFECOME point to figures exceeding 19,000 tonnes per day. This difference—nearly 30%—illustrates the lack of common methodologies and unified measurement systems.

Paradoxically, there is some consistency in waste composition data for Lagos, which reflects percentages very similar to national averages. This is striking, given that significant differences would be expected between a highly urbanised city and rural or agrarian areas.

Informal waste management is a key component in understanding this reality. In Lagos, much of the collection and recycling occurs outside the formal system: thousands of people work collecting, sorting, and selling recyclable waste without legal recognition or institutional integration. This parallel economy plays a vital role but also distorts statistics and complicates planning.

This is compounded by institutional fragmentation. In Lagos, responsibilities over waste are distributed among LAWMA (the state authority), private companies (PSP Operators), local governments, and the Ministry of Environment. This multiplicity of actors hinders data consolidation, oversight, and coordinated planning.

In short, the lack of reliable data on waste management in Nigeria and Lagos is not just a technical or administrative issue: it is a structural barrier that prevents progress toward sustainable, equitable, and resilient urban models. Overcoming it requires not only greater investment and technology but also a strong political commitment to transparency, evidence generation, and institutional strengthening. Without a solid informational foundation, any strategy is doomed to inefficiency.

Por Juanjo González Nieto